The title might sound like a spell straight out of Harry Potter (‘Wingardium Leviosa!’), but trust me it is not! It is a spell from Mathematics!

You might have come across some Interesting Facts while scrolling Instagram or the likes that the keys to the Internet are in the hands of around 10-20 people and 7 of them can bring the internet down. However outlandish that statement may sound, it is, to an extent, true. Relax! It isn’t the end of the world! The keys are signed every three months and will have very limited impact on the Internet if exposed at all. Just read this and stop panicking.

Back to the topic, the Shamir Secret Sharing System was developed (obviously) by Adi Shamir. The same Shamir from RSA (RSA is an encryption scheme that literally runs the internet; even if you don’t know what the heck I am talking about, be grateful that RSA is protecting your data across the web and beyond)! The system divides a secret (a secret is something you hide from everyone, if it is not apparent) into many different parts in the form of coordinates on a polynomial.

We then reconstruct the polynomial from the coordinates

Please don’t doze off! Let me try another approach! Does a story sound good? Okay!

You are the hero (note that ‘hero’ is gender-neutral) of this story. So, my little hero, you are a scientist working at a top secret research facility and have stumbled upon a really dangerous secret — a number, which is the password to the head scientist’s laptop.

Now that you have this dangerous number, you, like a good member of the society, want to share this number amongst other four of your peers so that you can bully Mr. Boss into giving you a few extra holidays.

Now, as a student of game theory, you know that your peers cannot be trusted and one (or more) of them could just go to the boss and snitch on you, putting all of you into a lot of trouble and earning the snitch a lot of blessings.

To preserve this number, you decide to use Shamir’s method. You once read it in Adi Shamir’s paper ‘How to Share a Secret’ and have been dying to implement it ever since.

Now, you can share the secret amongst scientists and you won’t be able to retrieve the number unless you have a number of scientists above a threshold consenting to unlock it. The secret number will be available only when atleast scientists put in their keys and rotate them.

This is called a threshold scheme.

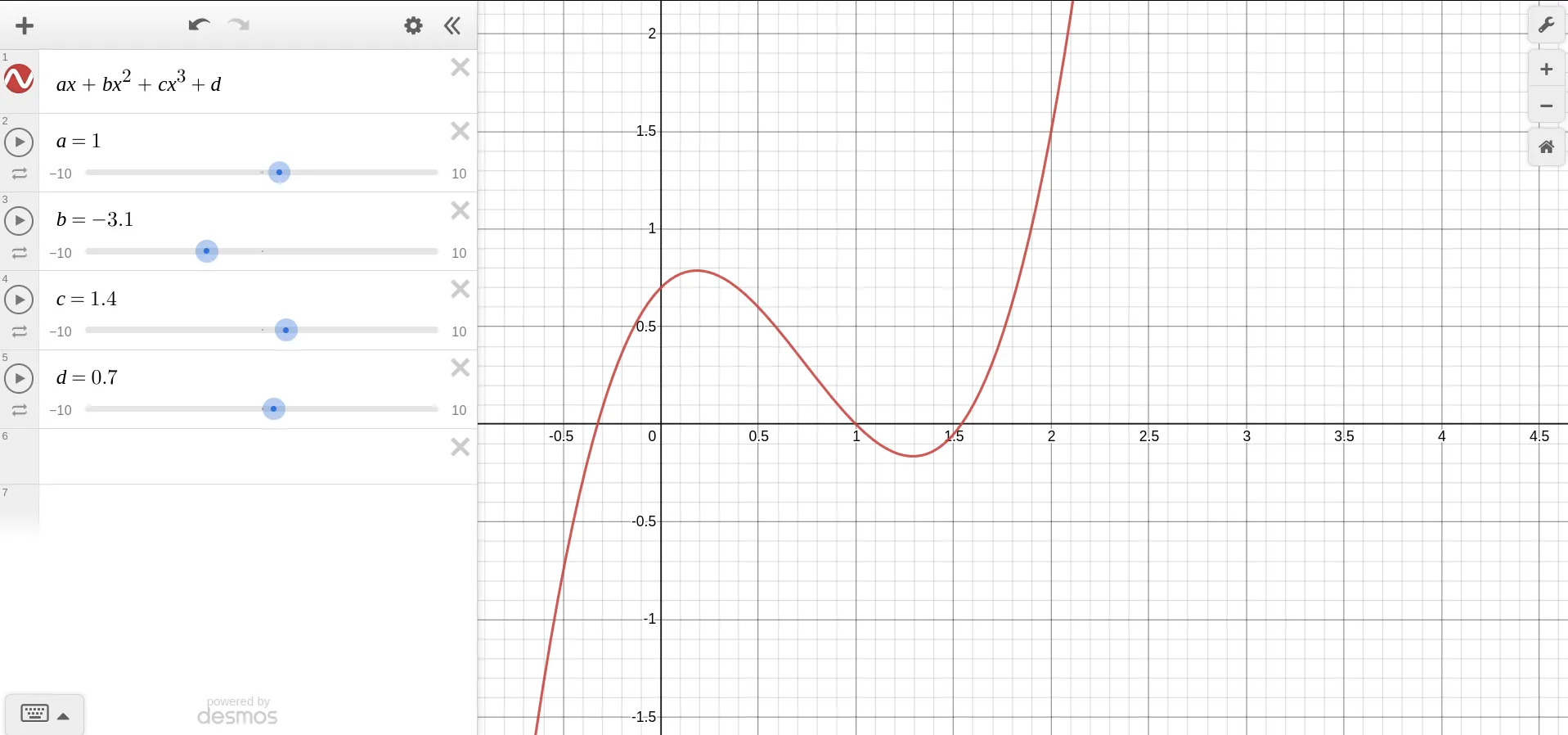

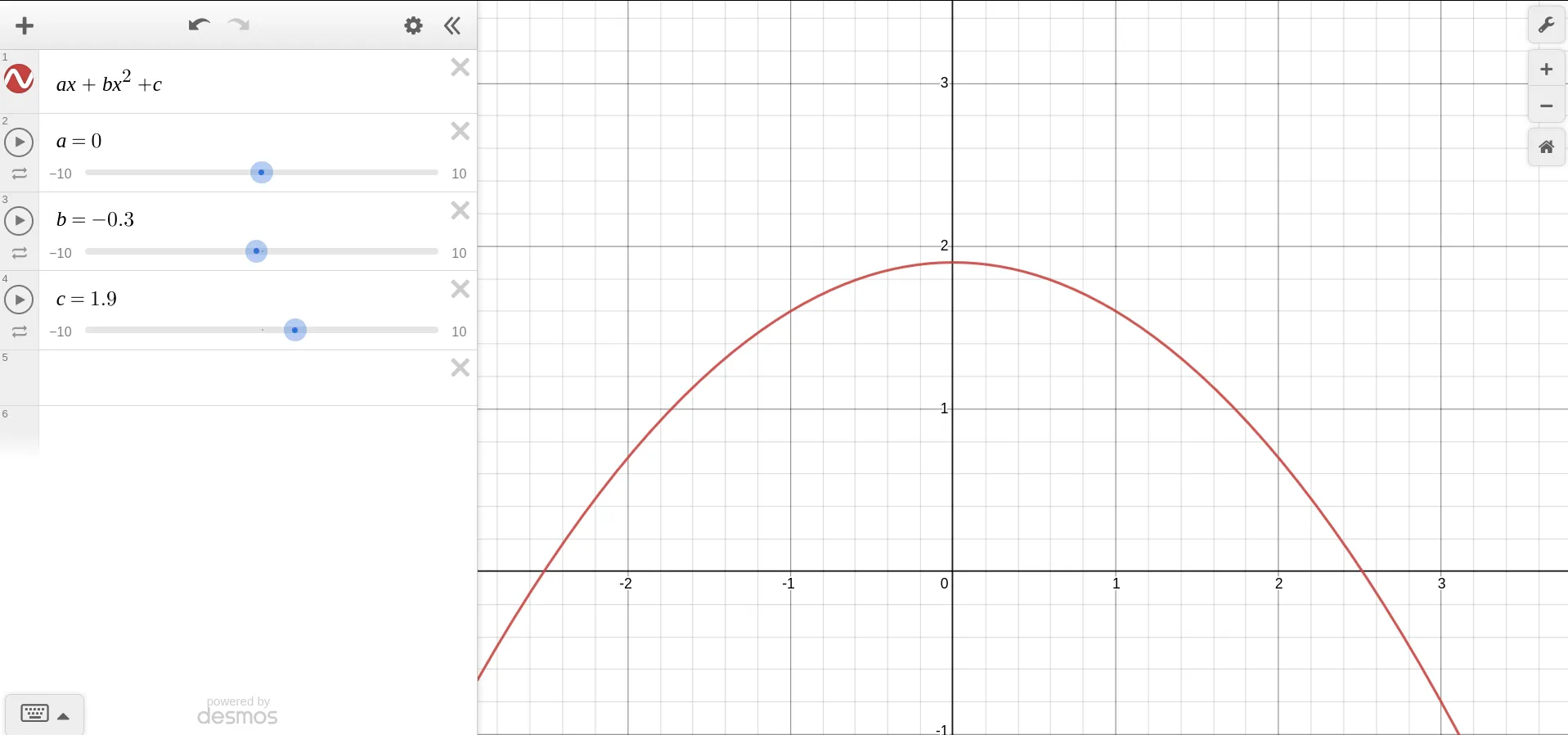

The technique involves passing the number as a constant inside a polynomial with random coefficients. If you have forgotten, a polynomial is an equation with a bunch of ‘s with increasing powers starting from one and attached to a number. Remember those quadratic equations with their elusive roots, those were polynomials! Polynomials are generally something like this:

They produce really awesome shapes depending on their coefficients and degree (the number of ‘s in the equation). Some of the are:

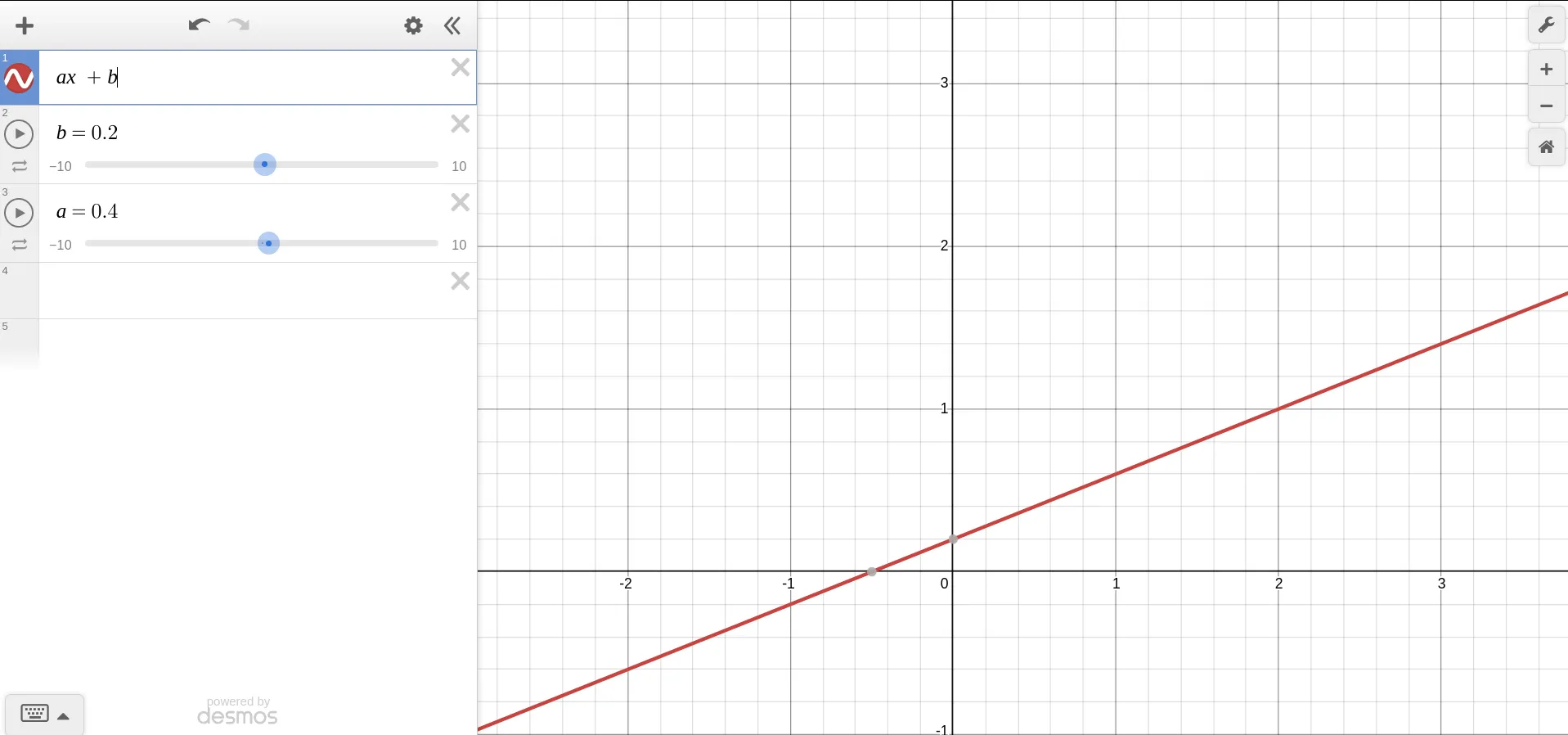

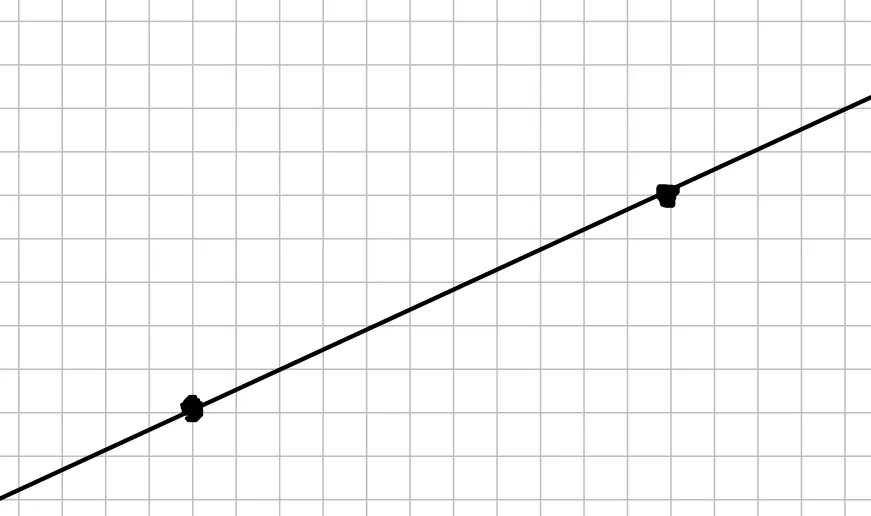

They can even be straight lines, where the highest power of is 1

“Wait a minute,” you might say, and storm away, feeling betrayed thinking that I just lured you into solving a bunch of maths while I promised you cryptography. Well, be patient.

The best thing is that polynomials aren’t all about their looks! Adi Shamir found a really good use for them. See, the thing with polynomials is that (given enough of them) we can reverse-engineer/reconstruct them from the points that lie on them. Let’s start with the most basic example: a line.

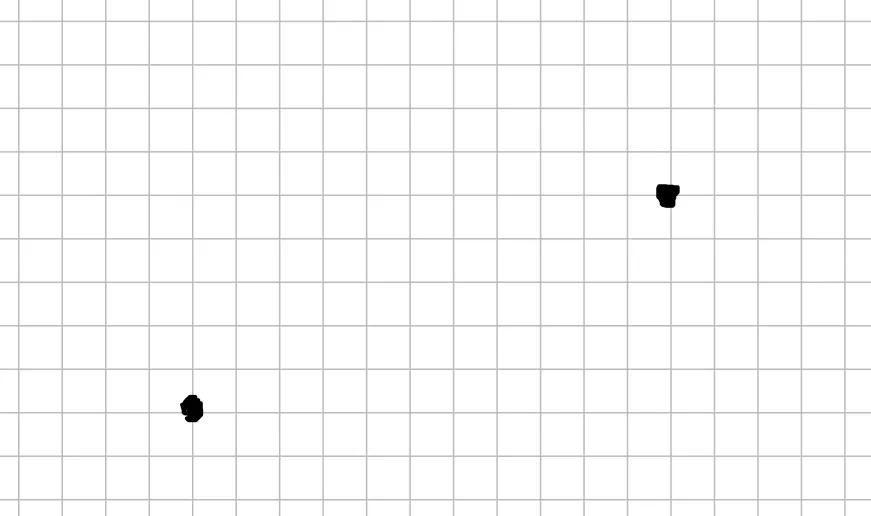

You have 2 points:

You can easily draw a line through them:

An important fact about this line is that it is distinct and no other lines can be produced from the given two points. Another fact is that if you have the line, you have the equation as well.

The same applies to polynomials of higher degrees. If you have points, you can draw a quadratic curve that passes through them. And those poins will always give you the same quadratic curve. In general, you can reconstruct an polynomial of degree if there are distinct points. Remember drawing curves for statistics in school when you would draw the points extra large so as to make the curves pass through them?

One more thing to note here is that you cannot reconstruct a distinct equation if you have less than points. You could draw all sorts of crazy shapes intersecting only two points, but none of them are distinct. You get an infinite number of quadratic equations passing through points, but there’s only one quadratic equation passing through points.

Now, the fun begins!

The Recipe

-

The first part of the process is

-

Hold the secret number firmly in your hand

-

Sneak it into the equation. You’ll know exactly why we are putting this number where we are in the equation when we reconstruct the secret. We are gonna divide the secret amongst the scientists. We will use a quadratic equation so that the minimum points (and thus scientists) need to retrieve the equation are as quadratic equations are of the degree and thus atleast points are needed to reconstruct the equation. Write the following equation down:

Here, and are completely random numbers. You will forget they ever existed after the first part of the process is done. Then you will have to reconstruct them in the second part. Randomness helps us in evading guesses.

-

We will assign as through for each scientist and enter the into the equation. Each scientist will get their own to make a sticker of and put on their laptop!

-

They have to preserve their pairs of ‘s and ‘s, called shares, if they ever want to retrieve the number.

-

Done! That’s all it takes to divide a secret! Now, unless atleast of the scientists are willing to retrieve the secret, say bye-bye to your vacations!

-

-

Your boss is overworking your entire team and all of you agree that something needs to be done about it. You take the lead.

-

Gather or more scientists (the more the merrier).

-

Take them to your ultra-safe safe where you kept the secret.

-

List the things that you know:

- The equation we used for the encryption was quadratic

- The keys (the ‘s and ‘s) you gave the scientists can be used to reconstruct the equation

-

Now, you have all the points, but you never gave a thought to the exact method of reconstructing the secret. You just intuitively knew what was gonna happen! Luckily, you have a scientist, who is a mathematician by night and who points you towards Lagrange’s formula. Lagrange was this 18th century dude who made this incredible method that solves the exact problem we are facing. It takes in a bunch of points, and, for each point, it creates this monstrosity:

is a term here for each of the points and is the point x-coordinate of the point we are using and all the other are the other points. We then multiply these ‘s with their respective ‘s and add them up! This gives us a function .

Believe it or not, P(x) is our original function! The one we had to bid farewell to when we were done sharing our secrets. It’s been so long!

-

We still don’t know how to reconstruct the secret. Let’s go back to the function’s original form:

Through our rebellious shenanigans, we know that:

You can now give any to and it will bounce happily and give you some number. But, we are looking at a really specific (and special) here. Close your eyes and think (open them if you forget the equation). Think. Think. Think!

Yep! You bright little kiddo! The special is , the secret ingredient of our secret recipe!

Thus:

-

Yep! You got your secret back and are on your way to Lonavala!

-

Getting Your Hands Dirty

You just beheld the miracles mathematics can do. If any of the concepts or mathematics bounced right over your head, you got me to blame.

By the way. here’s some code for you to experiment with in the Common Tongue:

- To share the secret and retrieve the shares:

import random

# ax^2 + bx + secret = y

a, b = random.randint(-10000, 10000), random.randint(-10000, 10000)

secret = int(input("Enter secret: "))

def get_y(x):

return a * x * x + b * x + secret

for i in range(1, 6):

print(f"The five parts of the secret are {i}, {get_y(i)}")- To reconstruct from the shares:

from functools import reduce

def lagrange(x, xys):

common_numerator = reduce(lambda x, y: x * y, [(x - xy[0]) for xy in xys], 1)

out = 0

for xy in xys:

print(out)

xn, yn = xy

current_term = 1

current_numerator = common_numerator // (x - xn)

current_denominator = reduce(

lambda xi, yi: xi * yi,

[(xn - xy[0]) if xn != xy[0] else 1 for xy in xys],

1,

)

current_term = (current_numerator / current_denominator) * xy[1]

print(current_numerator, current_denominator)

out += current_term

return out

xys = []

for i in range(5):

xi, yi = [int(i) for i in input(f"Enter x{i+1} and y{i+1}: ").split()]

xys.append([xi, yi])

print(lagrange(0, xys))You could increase the number of degrees of the equation (the threshold) or increase the participants or do all sorts of things.

Happy hacking!

Conclusion

You just learned a neat little trick to divide a secret amongst a number of participants while unwillingly facing a little maths with it. Fun fact: the co-founder of PayPal, Max Levchin, implemented the scheme in the early days of the company to secure the password to the company’s database, but it was later shelved when eBay acquired the company.